Old Vespas are very appealing to me. I love the way they feel. I love the way they smell. I love the curves on them.

|

|

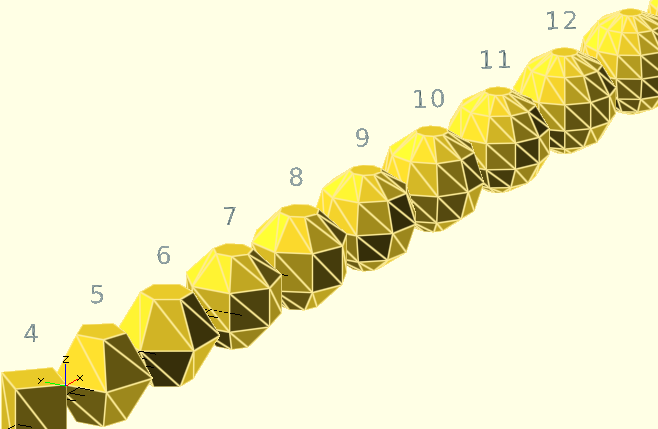

All 'Curve objects' in The GHOUL are nothing but 'lines' or curves with a cylindrical cross-section, even if the are 'in a 2D plane'. In The GHOUL, the 'resolution', or the number of segments in the cross-section of the curve object itself, is determined only by The GHOUL’s own special variable $fc, while in this respect $fn is entirely ignored. If $fc=0,

Segments() is used to determine the appropriate segment number.

|

This is the home of general curves. Bézier curves, and SVG curves and shapes, have their own pages. Some of the routines here are not necessarily curve 'generators', but may be so 'curve specific' that they really aren’t at home (any better) anywhere else, and thus reside here.

Circles and Arcs

|

|

Arcs are not circles. The following routines started out as one, but an arc has an endpoint, and a circle doesn’t. There’s no such thing as a 360 degree arc; an arc is part of a circle. "So what, who cares about linguistics? We’re 3D modelling here!" you say. Well, as with everything; if it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing it right, and this difference becomes essential when generating lists of vertices, as the endpoint of a 360 degree arc would overlap the starting point. So, there’s a reason 'in principle', as well as a practical one. It also makes for clearer code—IMNSHO—which is a bonus. |

Arc()

The Function

Arc(StartAngle,EndAngle,Radius,FullEnds=true,3D=false)

-

StartAngle, angle in degrees [0, 360] where the arc starts.

-

EndAngle, angle in degrees [0, 360] where the arc ends.

-

Radius, dimension, radius of the arc.

-

FullEnds, Boolean, if true, the arc 'n-gon' has endpoints with radius=Radius.

-

3D, Boolean, if true, vertices will receive 3 coordinates (with Z=0).

The Arc() function returns a list of vertices forming an arc.

Arcs and circles are really n-gons, made up of segments. By default, when the endpoints are somewhere between two of the n-gon corners, they are at full Radius. This gives 'deformed' ends to the n-gon arc, however, they join up with tangential lines to the 'theoretical' curve in that point, which is behaviour an unsuspecting user might expect…

If FullEnds=false, start and end points, regardless of whether they lie on a proper n-gon corner point, or somewhere in between, are located on the segment line proper, i.e., we’re literally cutting a segment from the n-gon, preserving the endpoint positions on the segment line.

The Module

Arc(StartAngle, EndAngle, Radius, Thickness, Pattern=undef, FullEnds=true)

-

StartAngle, angle in degrees [0, 360] where the arc starts.

-

EndAngle, angle in degrees [0, 360] where the arc ends.

-

Radius, dimension, radius of the arc.

-

Thickness, dimension, diameter of the 'drawn' curve.

-

Pattern, Tuple, dash-dot pattern in unit line lengths.

-

FullEnds, Boolean, if true, the arc 'n-gon' has endpoints with radius=Radius.

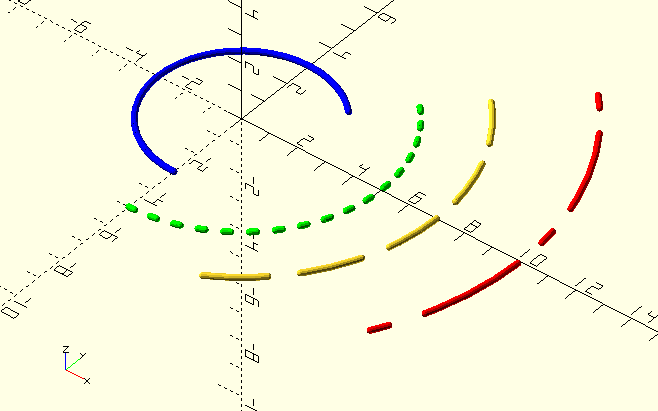

The Arc() module 'draws' an arc; it’s used in images to indicate pitch-circles and such. To get a dashed or dotted line, specify the pattern as a tuple of unit line lengths, e.g., [5,10] for 5 unit lines with 10 unit gaps, or [3,2,1,2] &c. The Pattern[0] and Pattern[even] elements are lines, the Pattern[odd] elements are gaps. If the pattern ends with a 'gap', Arc() adjusts the pattern length so the final arc will end with a line-segment, to prevent an 'undefined' end of the drawn arc.

ArcAngles()

ArcAngles(StartAngle=0,EndAngle=360,Radius)

-

StartAngle, scalar [0, 360], angle where the arc starts.

-

EndAngle, scalar [0,360], angle where the arc ends.

-

Radius, scalar, default is undefined, if specified, angles will be based on $fs or $fa, unless $fn is (locally) declared to be not 0 .

Divide an arc into segments and return the segment angles as a tuple. Angles are (obviously) from 0 to 360 with 0 on the X-axis, and the start-angle can be larger than the end-angle, e.g., for an arc from 270 to 90 degrees. Arcs always go in a CCW direction.

|

|

See the

sidebar at Segments() for a detailed explanation of how The GHOUL determines the size of segments and angles for arcs and circles. It’s very similar to the native OpenSCAD process, but there are subtle differences.

|

echo(ArcAngles(0,30,$fn=36)); // $fn=36 so segments will be 360/36=10 degrees.

ECHO: [0,10,20,30]Circle()

The Function

Circle (Radius,3D=false)

-

Radius, scalar, circle radius.

-

3D, Boolean, if true, vertices will receive 3 coordinates (with Z=0).

Returns an array of vertices forming a circle. As it’s mainly meant for generating shapes and polygons and such, it defaults to 2D coordinates.

The Module

Circle(Radius,Thickness+0.1,Pattern)

-

Radius, dimension, radius of the arc.

-

Thickness, dimension, diameter of the 'drawn' curve.

-

Pattern, Tuple, dash-dot pattern in unit line lengths, see comments at

Arc().

The Circle() module 'draws' a circle; it’s used in images to indicate pitch-circle diameters and such.

CircleAngles()

CircleAngles(Radius)

-

Radius, scalar, circle radius.

Like ArcAngles() this divides a circle into a set of angles and returns them in a tuple. See below at Segments() for a full explanation of the logic used to calculate the number of divisions.

Segments()

Segments(Radius)

-

Radius, scalar, optional, circle radius.

As a utility function, this really belongs in that section (below), but as it is the 'mother' of all circle-like routines here… Segments() returns the number of segments a circle should be divided into, based on the OpenSCAD special variables, $fa, $fn, and $fs, as well as The GHOUL’s own special variable $ff, which, if not 0, overrides the OpenSCAD special variables and determines the maximum fragment size, as explained in this sidebar:

Straight lines

ALine()

ALine(Angle,Thickness=0.05,2D=false)

-

Angle, scalar, Line angle CCW from the positive X-axis.

-

Thickness, scalar, line thickness (i.e. width!).

-

Color, OpenSCAD color identifier.

ALine() generates a 'line' through the origin in the Z=0 or X-Y plane, at a given angle to the positive X-axis. Also see HLine(), Line(), and VLine().

All these routines create 'lines'; thin cylinders, unless 2D is true in which case the lines are thin bands of rectangular cross-section, the top surface of which is the Z=0 plane, i.e., they lie beneath the plane. Used by modules such as Dimension() and GraphPaper().

HLine()

HLine(Y,Thickness=0.05,2D=false)

-

Y, scalar, value where the horizontal line crosses the Y-axis.

-

Thickness, scalar, line thickness (i.e. width!).

-

2D, Boolean, draw a '2D' line if true.

HLine() generates a 'line' parallel to the X-axis in the Z=0 or X-Y plane, through a given Y-value. Also see comments at ALine().

Line()

Line(P1,P2,Thickness=0.05,2D=false)

-

P1,P2, points, points between which the line is drawn.

-

Thickness, scalar, line thickness (i.e. width!).

-

Color, OpenSCAD color identifier.

Line() generates a 'line' between two points in the Z=0 or X-Y plane. Also see comments at ALine().

VLine()

VLine(X,Thickness=0.05,2D=false)

-

Y, scalar, value where the vertical line crosses the X-axis.

-

Thickness, scalar, line thickness (i.e. width!).

-

Color, OpenSCAD color identifier.

VLine() generates a 'line' parallel to the Y-axis in the Z=0 or X-Y plane, through a given X-value. Also see comments at ALine().

Utilities

CurveLength()

CurveLength(Array, Closed=false)

-

Array, array, vertices forming a curve.

-

Closed, Boolean, if true the curve is 'closed' and the distance between Array[n] and Array[0] is part thereof.

Returns the developed length of the curve, i.e., the sum of the distances between the successive vertices of the curve.

CurveOffset()

CurveOffset(Curve,Dist,Closed=true)

-

Curve, an array of 2D vertices, describing a curve.

-

Dist, a scalar; offset distance, positive is to the right of Curve when walking Curve beginning-to-end, if Curve is a polygon, this would make the polygon larger.

-

Closed, a Boolean; true if the curve is closed.

CurveOffset() takes a Curve, an array of vertices, and generates a new array, at Dist from Curve. The new array will lie to the right of Curve when 'looking' from the first vertex and Dist is positive.

Curve=[[10, 0],[5,8.7],[-5,8.7],[-10,0],[-5,-8.7],[5,-8.7]]

NewCurve=CurveOffset(Curve,1);

echo(NewCurve);

ECHO: [[11.5, 0], [5.8, 10], [-5.8, 10], [-11.5, 0], [-5.8, -10], [5.8, -10]]

// Note: Values in the above `echo()` output have been rounded to 1 decimal point for purrdyness purposes.FindCurveVertex()

FindCurveVertex(Curve, Distance, Closed)

-

Curve, array, vertices forming a curve.

-

Distance, distance from the beginning of the curve, i.e., Array[0].

-

Closed, Boolean, Array is a closed curve if true.

Returns the vertex at or before Distance. Takes 'lapping' of a closed curve into account.

TangentPoint()

TangentPoint(Vertex,Curve,Direction=1,Index)

-

Vertex, 2D vertex through (from) which the tangent runs.

-

Curve, vertex array describing a curve.

-

Direction, scalar, if not greater than 0, Curve is searched in reverse direction.

-

Index, integer, vertex from which to start searching. If left undefined, Curve is searched forward from the start if Direction is greater than 0, and backwards from the end if it is not.

Although it doesn’t return a curve, this routine is so closely related to curves that I had a hard time putting it anywhere else (Math and Logic?), so here it is. It searches Curve and returns the first vertex it finds to which the line drawn from Vertex is tangential. Curve can be searched in either direction, from either end, or starting from a certain vertex.

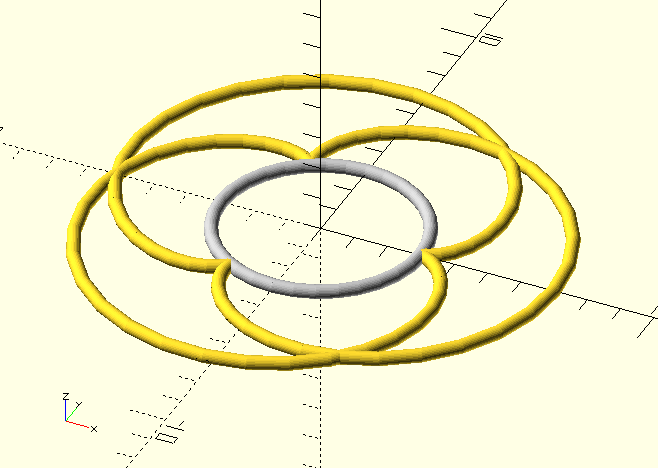

Roulettes

The file TheGHOUL/Lib/Curves/Roulettes.scad contains a number of roulette generating routines, most of which are not really user functions, but deserve attention anyway, because, this is The GHOUL, and nothing is left undocumented. Different kinds of roulettes are used to generate certain parts of tooth-profiles in involute and cycloid gears; also see the documentation at Gears and Clocks.

Roughly speaking, a roulette is the curve described by a point (called the generator or pole) attached to a given curve, as that curve rolls, without slipping, along a second given curve that is fixed.

In the case where the rolling curve is a line, and the generator is a point on the line, the roulette is called an involute of the fixed curve. If the rolling curve is a circle and the fixed curve is a line then the roulette is a trochoid. If, in this case, the point lies on the circle then the roulette is a cycloid.

There is further distinction between epi- and hypo-trochoids (curves outside and inside the fixed circle), and there appear to be several aliases and overlap in the naming—a cycloid is also referred to as a 'common trochoid'—not to mention 'centered trochoids', a moniker that appears to cover a multitude of sins. Then there are the limaçon, cardioid and nephroid, which—really—are all epitrochoids, the deltoid and astroid (which are hypocycloids) are also just (special cases of) hypotrochoids, and, finally (in this by-no-means-complete list), there’s the ellips, created by a circle of radius R rolling inside a circle of radius 2R, with a pole located at r<R. It’s jolly interesting, if you’re into that sort of thing; it made some people a good bit of dosh when they developed the Spirograph at any rate…

Trochoid()

Trochoid(R,r,d,Angle)

-

R, scalar, fixed circle radius.

-

r, scalar, rolling circle radius.

-

d, scalar, generator radius, i.e, the center of the rolling circle to the 'scribing' point.

A trochoid is the curve generated by a point, fixed to a circle which rolls around the inside (hypo-) or outside (epi-) of another, fixed, circle. The point ('pole' or 'generator') can sit on, inside or outside the rolling circle, yielding distinctly different curves. This routine is not here because of the pretty shapes it creates; Epitrochoid and Tusi couple curves are integral to the design of tooth and leaf profiles in clock-gears.

Involute()

Involute(BaseRadius,TipRadius,StartRadius)

-

BaseRadius, scalar, radius of the 'fixed circle'.

-

TipRadius, scalar, radius on which the tooth-tip lies.

-

StartRadius, scalar, radius to start the involute, if not BaseRadius. If left undef, the involute starts on BaseRadius.

You’ll probably not have much use for this routine, but—as you know—this is TheGHOUL, so it must be documented. Here’s a nice image demonstrating how the involute is constructed, and there’s TheGHOUL/DemoFiles/Img_Involute.scad as well, if you’re interested.